Read more

Ruzici honoured 40 years after victory

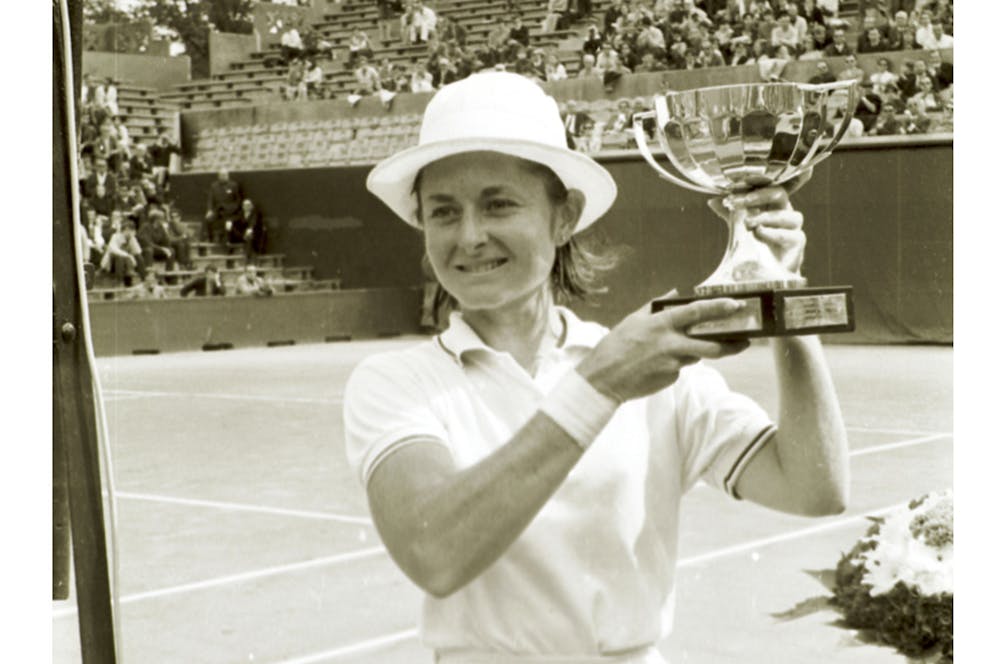

The American was the champion of the first "Open" Roland-Garros tournament 50 years ago, in 1968.

This year’s French Open marks 50 years since the first “Open” Grand Slam event, when the professionals were welcomed back into the fold, having been banned from major tournaments and Davis Cup and Fed Cup.

The era of “shamateurism”, when amateurs were paid money under the table in lieu of prize money had finally come to an end a couple of months before, after an extraordinary meeting of the International Lawn Tennis Federation (now the ITF), held in Paris.

Australian Ken Rosewall took the men’s title and earned 15,000 Francs (about $3,000 at the time), while the women’s champion, the American Nancy Richey, still an amateur, did not accept the prize money (of roughly half) for fear she might be banned from Fed Cup.

“The USTA did not allow the Americans to receive prize money in 1968,” Richey said in an interview by phone from her home in Texas. “They were still hanging on to the old amateur stuff. All I got was $27 a day per diem and I had to kind of fight for that. I wasn’t paid that (by the USTA) until I got to Wimbledon.”

But Richey’s memories of Paris in 1968 are warm and vivid, as you might expect for someone who won her first French Open title.

“It feels like yesterday,” she said. “Because of all the things that happened, it really sticks out on my mind. Australia, winning that (in 1967), I remember the final and all but it wasn’t a situation like what we experienced in Paris.”

The 1968 French Open was set amid the civil unrest that rocked Paris in May, 1968, when strikes, riots and protests made headline news around the world.

Richey remembers it as being “wild”. “I think when you’re young like that you don’t think a whole lot about the danger, if there was any,” she said. “I don’t remember seeing any demonstrations, it was just that everything was under lockdown. The garbage was piled up, just stacks of it, telephones were not working. I couldn’t call my Dad (who was also her coach) to talk to him during the tournament.”

It took a huge effort for Richey to even get to Roland-Garros in the first place.

“We played Federation Cup at Roland-Garros the week before the tournament so I was actually there three weeks,” she said. “They’d already shut down the airports (so) the team ended up flying to Brussels, we stayed there a day or two and practised, and then we got a bus from Brussels into Paris.”

But the upheaval didn’t affect her performances on the court.

In the semi-final, she came from a set down to beat Billie Jean King, thanks to her superior fitness and some advice offered by her brother, Cliff Richey, the former top-10 player, who reached the fourth round that year and helped her throughout the event.

“That was a tough match in Paris,” said Richey. “It was 4-4 in the third, and Cliff motioned for me to start attacking. Billie was getting really tired and made errors at that point, because of it.”

In the final, she recovered from a set and 4-1 down to beat the Briton, Ann Jones, who double-faulted on match point as Richey claimed a 5-7 6-4 6-1 win. “The Sunday I won it, that afternoon, the strikes lifted and I was able to call home and tell my Dad I’d won. Incredible timing,” she said.

As part of the Original 9 – the nine women who started what would eventually become the WTA Tour - Richey made a good living out of tennis. By today’s standards her earnings were modest, but she would not have had it any other way.

“For one thing, at 5'3", I couldn’t hold up with these six footers,” she said. “But also, I got to see all of the game. I got to see the amateur game, we started the pro game and I played in the pro game. It’s just an experience I wouldn’t want to trade.”