The second week of Wimbledon is almost upon us and the draw sheet is littered with new names. Not new to tennis, not new to success but new to the latter stages of the grass court extravaganza that is Wimbledon.

Grass? It’s mental!

The second week of Wimbledon is almost upon us and the draw sheet is littered with new names to the latter stages of the tournament.

©Corinne Dubreuil/FFT

©Corinne Dubreuil/FFTAthletic frame and mind

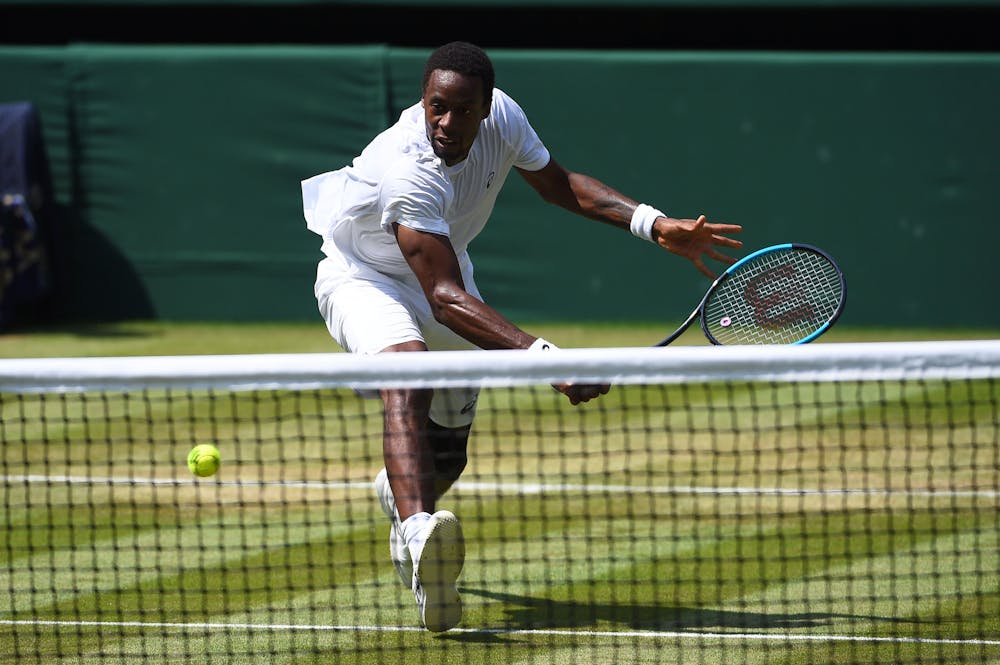

Among them, readying himself to take on Kevin Anderson, is Gael Monfils. An Australian Open and Roland Garros quarterfinalist, a US Open semifinalist and a former world No.6 (and that was only two years ago), Monfils has proved himself to be a threat wherever he goes, provided his body holds up to the strain. Everywhere except in south west London, that is. For an athlete of Monfils’s calibre, that seems strange. But maybe not.

What governs Monfils and his athletic frame is his mind: when it is focused on the job in hand, he is a magnificent player. When the stuff between his ears turns to scrambled egg, he can lose to anyone. And until now, his brain has not been able to process the intricacies of playing on that funny green stuff the Brits love so much.

Age – he is now 31 – and experience are beginning to tell, though. He beat Sam Querrey, a semifinalist last year, in four sets on Friday to set up his appointment with Anderson. Apart from a minor injury scare, it was an impressively solid performance. How had he done this? Simple: belief. It was all in the mind. He had finally come to the conclusion that he could, indeed, play on grass.

“I think it took me years and years,” he said. “Also had to put myself in a good opportunity, to put myself in a good balance with my body and my belief on a grass court. I just couldn't I think take the opportunity. Today I took it and I'm happy about it.”

©Corinne Dubreuil/FFT

©Corinne Dubreuil/FFTIs grass an alien?

Tennis players are creatures of habit. They really do not like change. They have their habits and superstitions and they stick to them religiously. They eat the same meals, shower in the same cubicle, wear the same lucky socks – it sounds crazy but it seems to work for them.

Of course there are drawbacks to this: “I had a ham bap and a jammy dodger before I beat Mable Butterthwaite from accounts. I’ve had the same lunch ever since in the hope that it happens again. Trouble is, I beat her in 1947… I’m getting a bit sick of it now….” But let us move on.

So, when the tour moves from clay to the mad, five weeks of the grass court season, the players split neatly into two groups. There are those who take their first look at the pristine, green courts and think “oh, goody… this will be fun” and then somehow find a way to adapt their game to the slicker surface. Then there are those who recoil in fear: “grass is alien…I will never be able to play here”. As a result, they fail with monotonous regularity. Those first impressions are hard to shift.

The greats, though, find a way through it. Roger Federer took to grass like a duck to water and is now chasing his ninth Wimbledon title. Rafa Nadal liked the idea of grass and went away and taught himself how to play on it (he is chasing his third title). Novak Djokovic basically plays a hard court game – with a few tweaks – on the green stuff and is dreaming of a fourth title.

Even by @rogerfederer's standards, this drop shot was one of his finest 👏#Wimbledon pic.twitter.com/KtCYN0yxxI

— Wimbledon (@Wimbledon) July 4, 2018

Even Pete Sampras thought grass was weird at first. As we all know, he did come to love it in the end. Serena Williams, who loves Wimbledon and all that goes with it, has said in the past that while she is good a playing on grass, it is not her surface of choice. Not that it seems to have stopped her this year. Or, indeed, in any year that she has played in SW19.

Who has a traditional grass court game?

Going back to Sampras – his mental block was clay. This was the dreaded surface that scuppered his hopes every year. He was a fast court man, a serve and volley juggernaut. Clay was the Kryptonite that rendered him helpless. In 13 attempts, he reached just one semifinal at Roland-Garros. He just could not get his head around the red dirt of Paris.

Roger Federer vs Pete Sampras: Wimbledon fourth round, 2001 (Extended Hi... https://t.co/BW3z7HZVK4 via @YouTube

— J Martin (@JMartin44435686) July 8, 2018

Others found a way – Michael Stich served and volleyed his way to the 1996 final. Even Tim Henman got to the semifinals in 2004 working on the theory that if he could not play clay court tennis like a clay courter, he would play his game, his way, and see what happened. Until that point, he had never reached the second week of a slam anywhere but Wimbledon before.

Andre Agassi was the same. Was he going to slide like a dirtballer at Roland-Garros? Nah. And he won in 1999. Was he going to serve and volley like Sampras at Wimbledon? Nah. And he won in 1992.

These days, only a tiny handful of players have a traditional grass court game and while they provide great entertainment, they seldom go far in SW19. Dustin Brown and Mischa Zverev are fabulous fun to watch but they do not have what it takes to win major titles in the modern game.

Wimbledon is won in the same way that the US and Australian Opens are won: power and precision from the back, a deadly return and the courage and nous to know when to attack. Of course the movement is different but the movement is different on a hard court and a clay court yet most players happily switch from cement to brick dust without thinking twice.

Grass court tennis is not mental in the British meaning of the word (mad, bonkers, crackers) but in the dictionary definition of the word – cerebral, rational, intellectual. Get your head around the idea of playing on the green stuff and all will be well. Well, it will be unless you run into Roger, Rafa or Novak. But that is the same on any surface in any part of the world. That’s just tennis.

ROLAND-GARROS

20 May - 9 June 2024

ROLAND-GARROS

20 May - 9 June 2024